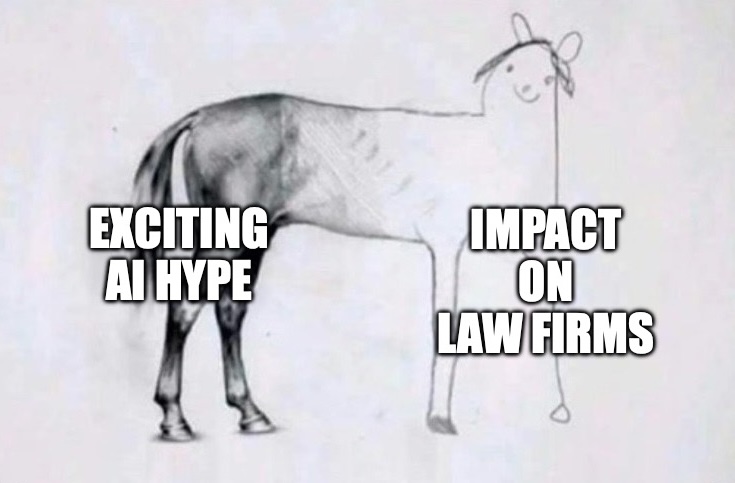

The idea that 25 year-old rookie solicitors earning nearly £200,000 are ripe for replacement by tech is appealing, but likely to be wrong

In 2017 I remember a partner at a large City of London law firm telling me confidently that trainee numbers were about to be decimated due to AI, then in its ‘machine learning’ incarnation.

Within five years, the partner asserted, trainee solicitors would number a mere third of what they are today, as all but the very best law graduates find themselves forced to settle for a life of tech-enabled paralegaldom. Partners, she added, would be fine.

Eight years on and legal trainee numbers are at record highs — and so are the salaries. As Legal Cheek’s Firm’s Most List documents, newly qualified solicitors at several US firms in London can expect to earn as much as £180,000, while the Magic Circle all pay a base rate of £150,000 these days. Even with inflation that’s a big jump on 2017 levels, when most of the top firms paid NQs well below £100k. Certainly, these figures suggest that the age-old corporate law firm pyramid model — which sees large numbers of trainees recruited and trained before a high rate of attrition kicks in as a lucky and hard-working few make to the partnership — is still doing rather well.

But now those conversations about AI disrupting law firms are back, as the latest version of the technology, ChatGPT-style generative AI, works its way into legal tech products. At an AI breakfast for journalists this week hosted by Simmons & Simmons, the partners knew better than to make wild predictions, but the vibe was similar to 2017. There was talk about lawyers learning to code, a cheerily unnerving emphasis on “adaptability” and even an admission that “we might need to rethink the commercial model for training junior lawyers because less of their time might be capable of being monetised”.

But a story told by senior partner Julian Taylor suggested that the need for such rethinking may be some way off. Taylor, an employment lawyer when not steering the Simmons & Simmons ship, relayed how he was recently having a late afternoon call with a client when a twist in the case saw a new 40+ page document come in that required swift analysis. Before the advent of Simmons’ new generative AI tool ‘Percy’ (named after one of the twin brothers who co-founded the firm in 1896), that would have meant a long evening for an unlucky junior associate. But with Percy, Taylor was able to upload the document to be analysed and have a pithy summary emailed over to the impressed client while still on the phone with them. How much did he charge for this wizardry?

“Nothing,” he revealed, adding: “Maybe the lesson from AI is that law firms are moving to a charitable model!”

The unspoken bit was that the document surely had to be read by the junior associate, and possibly other Simmons lawyers working on the case, just not that evening. And I don’t doubt that they charged for their time doing so.

Indeed, as Taylor went on to note, his corporate clients consistently tell him that they “don’t completely trust” AI and want people (i.e. the top percentage of grads that leading law firms fight it out over each year) handling the big-money, high-stakes cases and deals they send his firm’s way. In other words, AI might be fun, impressive, useful on the margins and even helpful for lawyer wellbeing, but it’s not what clients go to Simmons & Simmons — and other top law firms — for.

For those truly interested in the disruption of legal services, the place to focus on is the clients themselves. For it’s at these big companies where legal is of course not a generator of revenue, but a cost to the business, meaning real incentives lie to embrace AI to reduce spend on lawyers. What’s more, in-house legal teams tend to focus on more routine tasks where the odd AI hallucination may be less likely to result in a professional negligence claim.

As tempting as the idea may be that 25 year-old private practice lawyers earning close to £200,000 are ripe for replacement by tech, the reality is that it may be the mid-career lawyers who’ve stepped off the law firm gravy train to move in-house who find themselves most exposed.