The controversial proposals are a step too far, writes Oxford graduate and aspiring barrister James Cox

On 14 September the most live threat to our fundamental right to protest in recent decades, the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (PCSC), will have its second reading in the House of Lords. The threat is threefold: the introduction of noise as a trigger for unlimited police-imposed conditions on protest, a new statutory offence of public nuisance, and the beefing-up of penalties for those in breach of the rules. Further, the evidence points to the fact that the bill is the product of a government attempt to clamp down on the freedom to protest.

Introduction of a ‘noise trigger’

Currently, under the Public Order Act 1986, the police have the power to impose conditions on public assemblies which can be triggered by an officer’s reasonable belief there may be serious damage to property, serious public disorder, or serious disruption to community life. The PCSC proposes a fourth, broader trigger for this power: noise. The so-called ‘noise trigger’ allows police to impose conditions on public assemblies if an officer reasonably believes that the noise it produces may “result in serious disruption to the activities of an organisation which are carried on in the vicinity”, or “may have a significant and relevant impact on persons in the vicinity” where this impact includes causing “serious unease, alarm or distress”.

The threat here is the introduction of an alarmingly low threshold for triggering police control of protests: noise is an almost unavoidable, and often desirable, by-product of protest. Just as alarmingly, under the PCSC the meaning of this vaguely worded trigger (as well as the meaning of an existing trigger: “serious disruption to the life of the community”) is controlled, through Regulations, by the Home Secretary. The power to make such regulations (which are a form of secondary legislation) hands the government the power to clarify “serious disruption” and potentially target the effects of protests of specific groups and, more generally, facilitate greater control over acceptable public expression.

The PCSC also hands the police more control over protests when their powers are triggered, expanding their previous control over place, maximum number, or maximum duration of an assembly (S.14(1) POA 1986) to allow them to impose any conditions that the senior officer on the scene regards as “necessary to prevent such disorder, damage, disruption or intimidation”. Police would also be permitted to take action against “one-man protests”. Such changes, in the words of Professor David Mead, render protest “far more in the gift of the police”, something which, as he points out, events such as police actions at the Sarah Everard vigil should highlight the danger of.

As the Court of Appeal held in R (Singh) v CC West Midlands Police (2006), protest “becomes effectively worthless if the protestor’s choice of ‘when and where’ to protest is not respected as far as possible”. Under the PCSC, it is plainly not.

Statutory offence of causing public nuisance

The PCSC does away with the common law offence of public nuisance and replaces it with a broad statutory offence involving any “act that, intentionally or recklessly, causes serious harm to the public or puts them at risk of such harm”. Here, “serious harm” includes where a person suffers “serious annoyance, serious inconvenience or serious loss of amenity”, and the offence would also include “conduct which endangers the… comfort of a section of the public”. Further, statutory public nuisance would carry an extremely high maximum sentence of ten years, given that when the common law offence was used to target protestors, such as in Roberts, Blevins & Loizou v R (2018), the court quashed the use of custodial sentences as “manifestly excessive”.

Want to write for the Legal Cheek Journal?

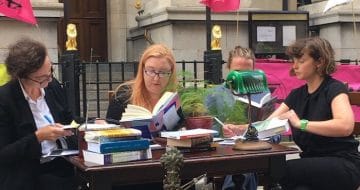

Find out moreGiven that many protests “obstruct” the public, cause “annoyance” or “endanger the… comfort of a section of the public” (indeed, this seems to be the whole point of protest), the offence allows for the criminalisation of close to the full range of public demonstration as public nuisance. Not to mention, the notion of being “criminally annoying” demonstrates the intolerance the government has for those they regard as “uncooperative”. Further, as Protest Matters points out, the PCSC revives the “almost… redundant” offence of public nuisance. Given the clear contempt the current government holds for protest, it does not seem a stretch to suggest that the revival of this offence (and in such a broad form) is simply designed to equip police and prosecutors with greater ability to crack down on “dreadful” BLM protests and those “uncooperative crusties” and “importunate nose-ringed climate change protestors” at Extinction Rebellion.

In the words of Lord Justice Laws, quoted in evidence by Adam Wagner at the committee stage of the PCSC’s progress through parliament, “rights worth having are unruly things. Demonstrations and protests are liable to be a nuisance. They are liable to be inconvenient and tiresome, or at least perceived as such by others who are out of sympathy with them”. Protest will inevitably be annoying to someone. To allow this to be a reason to clamp down on one of the most important engines of social progress shows profound arrogance and intolerance. It is these two characteristics that are the true hallmarks of this bill.

Increased penalties

The PCSC proposes heavy increases for a number of penalties for actions conducted by protestors. Most prominently, the consideration of monetary value when sentencing the “destroying or damaging [of] a memorial” has been removed, allowing the imposition of a maximum of ten years imprisonment (under the Criminal Damage Act 1971) in all cases. As has become the pattern, the PCSC defines “memorial” broadly so as to include anything “erected or installed on land” as well as “any moveable thing (such as a bunch of flowers)”, with a “commemorative purpose”, placed on it. This commemorative purpose can be for persons, animals (both living and dead) or events. As such, the perpetrator of almost any level of damage (e.g. graffiti) to just about any statute, and many placards, signs and even flowers, is liable to ten years imprisonment.

It is hard to regard this change as anything other than a direct response to recent movements against statutes commemorating those involved in the slave trade and, in particular, the toppling of an Edward Colston statue during a BLM protest in Bristol. Yet again, we see the bill for what it is: a politically motivated clamp down on movements with which this government takes issue.

While many Tory MPs have pointed out that ten years is a maximum, the removal of the notion of punishment proportional to damage (which seems the only sensible way to punish) leaves the government open to pursue punishment according to enmity. Garden Court Chambers highlights how governments have been traditionally willing to vigorously pursue the maximum charges and penalties available when prosecuting hostile activists, such as the Stansted 15 who were charged under an act designed to suppress terrorism at airports with a maximum sentence of life-imprisonment. Such changes to penalties allow the government greater scope for punishing political dissenters how they see fit.

A clamp down on protest?

The motives of the government become clearer when one considers the surrounding context. The current government, particularly Boris Johnson and Priti Patel, have never been coy about their dislike for protestors and their frustration with certain movements has become increasingly obvious. This, combined with the explicit concession by current cabinet member, Sajid Javid (while he was Home Secretary), that “where a crime is committed [during a protest] the police [already] have the powers to act”, and that there is significant legislation that “already exists to restrict protest activities that cause harm to others”, must lead one to the conclusion that the PCSC is designed to attack protest that would otherwise not be regarded as criminal. That is, there is no need for this bill for any reason other than a politically motivated clamp down on dissenters. Indeed, as Garden Court Chambers suggests, “the suggested ‘gaps in the law’ simply do not exist… These additional powers are designed to make it prohibitively difficult for the public to exercise its right to protest at all”.

Protest is a fundamental democratic freedom and a vital source of social progress. As such, for a government to take what seem to be intentional steps to curb it is highly disturbing. For all the government assurances that the right to protest will be protected, examination of the content of the bill makes it hard for one to join them in reaching this conclusion. The effect of the bill, as Kenan Malik has warned, would be to reduce the right to protest to a right to “whisper[ing] in the corner”. This is something we should all, regardless of political stripe, be concerned about.

James Cox is an aspiring barrister. He is a graduate in Philosophy, Politics and Economics from the University of Oxford and a Lord Bowen scholar of Lincoln’s Inn. He will commence the GDL at City, University of London in September 2021.

Please bear in mind that the authors of many Legal Cheek Journal pieces are at the beginning of their career. We'd be grateful if you could keep your comments constructive.