Nottingham law grad Fraser Collingham considers how the law balances free speech and offensive social media messages

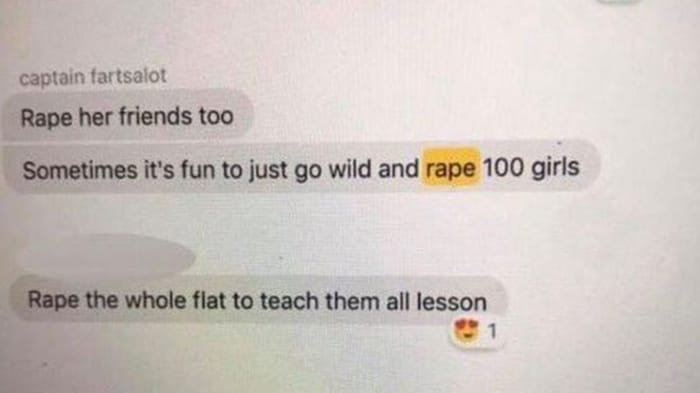

Freedom of speech is a highly contentious issue on university campuses right now. Recently, 98 expletive-ridden messages in a group chat were exposed, which made reprehensible racist, anti-Semitic remarks and jokes about raping female students. The participants in the chat were students at the University of Warwick.

This is the second group chat to be exposed to the mainstream media, with the Exeter law student racist group chat coming to light last year.

If these messages were sent directly to the females referred to, then it is highly likely the students concerned would face prosecution. The Warwick incident raises several interesting legal questions. Namely, the messages were sent in a private Facebook group chat that were then later exposed (presumably without the consent of all of the participants). No one has been charged as of yet. In fact, two of the 11 students were permitted to return to the University in September but have since decided against this.

The vice chancellor of Warwick University has said there was a “high likelihood” legal action would be taken. But has an offence been committed? And if so, should the students be prosecuted?

The law

Communications Act 2003

The starting point for the Criminal Prosecution Service (CPS) is section 127(1) of the Communications Act 2003. A person will be guilty of an offence if they “send by means of a public electronic communications network a message… that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character”. There is no need for it to be received. No victim is required. It has been held that Twitter is a public communications network (despite it being run on private servers) — so this Facebook chat would probably qualify too.

The key here is whether the messages were ‘grossly offensive’ — merely offensive is not enough. Grossly offensive is measured against “reasonably enlightened, but not perfectionist, contemporary standards” (DPP v Collins).

It must be emphasised that “satirical [or] rude comment… banter or humour, even if distasteful to some or painful to those subjected to it” will not be caught by section 127 (Chambers v DPP).

The offence is one of basic intent. The defendant must either intend the message to be grossly offensive, or at least be aware that a reasonable member of the public would view them to be so.

I think these messages, taken in their totality, would qualify as grossly offensive, based on DPP v Collins and Chambers v DPP. An offence under section 127 could therefore have been committed.

Malicious Communications Act 1988

This is another possible offence. Section 1 of the Malicious Communications Act 1988 prescribes a person who sends another person an electronic communication message which is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character will be guilty of an offence if their purpose (or one of their purposes) in sending it is to cause distress or anxiety to the recipient or to any other person to whom he intends that its contents or nature should be communicated. Nothing requires the communication to be received.

This is couched in very wide terms but here, I doubt the participants in the group chat intended their messages to actually cause distress or anxiety. They probably viewed their messages as jokes. Due to the specific intent requirement of this section (Chambers v DPP), I don’t think an offence has been committed here.

It is worth noting that the CPS has an arsenal of other offences at their disposal, contained in the Public Order Act 1986 and the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. The two offences outlined above I believe to be the most relevant.

Freedom of expression

This is enshrined in Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). It is a qualified right but the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has been very clear that it applies to information and ideas that offend, shock or disturb. (Handyside v UK, Vereinigung Bildender Künstler v Austria).

Prosecutorial guidance

Due to the extremely wide statutory drafting of section 127(1), prosecutorial discretion is key. The CPS initially struggled with the legislation, as was the case when Paul Chambers, an accountant, was initially found guilty of sending a menacing tweet but later won the High Court challenge against his conviction. Now, prosecutors can look to guidelines when determining whether prosecution in cases involving communications sent via social media is appropriate.

Evidential stage

The next step is the evidential stage in which there is a high evidential threshold. The CPS will only prosecute under section 127 where interference with freedom of expression is “unquestionably prescribed by law, is necessary and is proportionate”. Context is key.

Prosecutions will only be appropriate where the communication is more than offensive, shocking or disturbing; or more than satirical, iconoclastic or rude comment; or more than the expression of unpopular or unfashionable opinion about serious or trivial matters.

This is so, even if distasteful to some or painful to those subjected to it. Do the rape messages here go beyond the “pale of what is tolerable in society?” (DPP v Collins, Smith v ADVFN).

Kier Starmer, former director of public prosecutions (DPP) and CPS head, explicitly recognised that “banter, jokes and offensive comments” are “commonplace and often spontaneous”. It is relevant for prosecutors to consider:

• The way in which the communications were made

• The intended audience

• The application or use of any privacy settings

• The intention of those who posted the communications.

The individuals here may genuinely not have intended that their messages reach a wide audience — it was a private group chat.

Public interest stage

The CPS must then believe that it is in the public interest to prosecute. Since Article 10 ECHR is relevant here, on the particular facts of the case, it must be ‘convincingly’ established that a prosecution is ‘necessary and proportionate’.

Relevant factors include:

• The suspects’ age and maturity

• Whether the suspects have expressed genuine remorse

• The circumstances of, and the harm caused to, the victim

• Whether the communication was or was not intended for a wide audience, or whether that was an obvious consequence of sending the communication.

This last point is particularly important here.

Viable prosecution or thought crime?

The group chat participants may have committed an offence under section 127(1) of the Communications Act 2003, which is drafted very broadly. The students could be charged if the CPS decide that the messages are more than offensive, shocking or disturbing, do go beyond what is tolerable in society, and if it is in the public interest to prosecute.

It may be relevant that there have been protests by students, the fact that a second group chat has allegedly been created (showing no remorse) and several individuals have expressed their disgust and even fear to return to Warwick University’s campus.

Please bear in mind that the authors of many Legal Cheek Journal pieces are at the beginning of their career. We'd be grateful if you could keep your comments constructive.