Aspiring barrister Benjamin Ramsey explores the recent events involving Dinah Rose QC and David Perry QC

In recent weeks, the ethical conundrum of whether or not a barrister should take on a case has been thrust back into the spotlight.

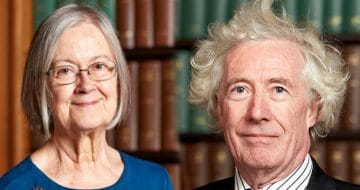

Two of England’s top QC’s, Dinah Rose and David Perry, have been criticised for accepting instructions to act in cases in which the parties they represent have questionable beliefs and practices. This article seeks to demonstrate the legal and ethical framework that surrounds the decision whether or not to accept a case, whether a barrister has any say in the matter and whether Rose QC and Perry QC were right to do so.

Dinah Rose QC

The Cayman Islands government first instructed Rose QC in 2019. Two women, Chantelle Day and Vickie Bodden Bush challenged Section 14(1) of the Cayman Islands constitution which states:

(1) Government shall respect the right of every unmarried man and woman of marriageable age (as determined by law) freely to marry a person of the opposite sex and found a family.

Ms Day and Ms Bush sought a marriage licence under the protection of Section 14(1). Ultimately, the Island’s Court of Appeal dismissed their challenge. However, the court held that same-sex couples were entitled to the same legal protections as marriage, with civil partnership legislation being brought in soon after.

On 23 February, the case will return to the Court of Appeal in a hearing before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The central question the court will consider is:

(1) Does the Bill of Rights in the Constitution of the Cayman Islands require that the marriagelaw of the Cayman Islands be interpreted so as to define “marriage” to include the union of same-sex couples?

Some commentators have stated that in accepting the instructions to represent the Cayman Islands, Rose is “prosecut[ing] a homophobic case to deny LGBTIQ persons in the Cayman Islands equal rights”. Due to the questionable beliefs on the part of the government, they say Rose should withdraw from the case as the ‘cab-rank’ rule does not apply.

The ‘cab-rank’ rule

The rule is named after the concept that a taxi driver, waiting in a cab-rank, must take the next passenger he gets, regardless of who he/she is and where they want to go. The rule applies to barristers and is a professional obligation to accept instructions from every client regardless of their view of the case or the personal views of the client.

The bar’s cab-rank rule is located in rule C29 of the current Bar Standards Board handbook (BSB). C29 states:

If you receive instructions from a professional client, and you are:

.1 a self-employed barrister instructed by a professional client…

…and the instructions are appropriate taking into account the experience, seniority and/or field of practice of yourself … you must, subject to rule rC30 below, accept the instructions addressed specifically to you, irrespective of:.a the identity of the client;

.b the nature of the case to which the instructions relate;

.c whether the client is paying privately or is publicly funded; and

.d any belief or opinion which you may have formed as to the character, reputation, cause, conduct, guilt or innocence of the client.

There are, however, several exceptions to this rule which are found in C30. The most relevant to Rose’s case are:

The cab rank rule rC29 does not apply if…

.5 accepting the instructions would require you to do any foreign work; or

.6 accepting the instructions would require you to act for a foreign lawyer…

‘Foreign work’ is described as providing legal services “relating to… court… proceedings taking place… outside England and Wales”. The Cayman Islands are a British Overseas Territory. Also, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council is based in London and falls under the jurisdiction of English law. Therefore, Rose’s instruction does not require her to undertake ‘foreign work’, having been instructed on several occasions to appear before the committee previously.

Want to write for the Legal Cheek Journal?

Find out moreThe second exception of acting as a ‘foreign lawyer’ is more troublesome. If Rose is acting for the Attorney General of the Cayman Island directly, then Rose would be acting as a ‘foreign lawyer’. However, if Rose has been instructed by English solicitors, then the exception would not apply and Rose would be obligated to accept the instructions. Truthfully, we do not know the answer.

In any event, the principle of providing legal services, provided the barrister is available and the case is within their knowledge and expertise, goes far beyond the ‘cab-rank’ rule. The need for a barrister to be independent and not discriminate is woven into the BSB handbook. Within the handbook ten core duties underpin the ethical framework and set the standards by which all barristers operate. Of these ten, core duty 4: You must maintain independence and core duty 8: You must not discriminate unlawfully against any person, are the most applicable to this situation. Also, rule C28 is the ‘requirement not to discriminate’:

You must not withhold your services or permit your services to be withheld:

.1 on the ground that the nature of the case is objectionable to you or to any section of the public;

.2 on the ground that the conduct, opinions or beliefs of the prospective client are unacceptable to you or to any section of the public…

Even if Rose was acting as a foreign lawyer and, therefore, not bound by the cab-rank rule, there is a potential risk she could fall foul of C28 those core duties. Some may argue Rose could be giving in to external external pressure and withholding her services due to the so-called ‘homophobic case’ of the Cayman Island government. It could also be viewed as potentially discriminating against a client due to its stance in the case and be letting the opinions of others sway her decision making. These, in turn, could compromise her independence.

David Perry QC

Rose’s case can be contrasted with the recent controversies surrounding David Perry QC. Perry accepted instructions to prosecute pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong. One of the defendants in the case is Martin Lee QC, the founder of the pro-democracy party in Hong Kong, having been accused of taking part in ‘illegal assembly’. In contrast to Rose’s case, the ‘cab-rank’ rule does not apply here. Having been instructed by the Hong Kong Justice Department, this is clearly ‘foreign work’, thus falls under the exceptions to the rule in C30. While Perry has undertaken several cases in Hong Kong previously, he is not a member of the Hong Kong bar, so the ‘cab-rank’ rule does not apply.

Interestingly, where Rose was steadfast in her position to remain instructed, Perry has now withdrawn from the case, following similar criticism. It is arguable that, by withdrawing, Perry has withheld his services on the ground that the conduct, opinion or beliefs of the government are unacceptable to a section of the public, hence the criticism. Therefore he may have breached rule C28, the requirement not to discriminate. However, there are also other core duties which state all barristers must act with honesty and integrity and must not behave in a way that that is likely to diminish the trust and confidence the public places in the profession. Acting for the Chinese government, in this case, could be contrary to those core duties. The rules within the handbook, therefore, appear to be at odds with each other.

The guidance note for C28, gC88, has the answer. It states:

‘…This rule of conduct is concerned with a broader obligation not to withhold your services on grounds that are inherently inconsistent with your role in upholding access to justice and the rule of law and therefore in this rule “discriminate” is used in this broader sense.’

Therefore, a barrister can withhold their services and not breach C28 if, by doing so, they are upholding access to justice and the rule of law. Arguably, the Chinese government’s prosecution of individuals for actions that are lawful under any reasonable standard of international or national law manifestly undermines the rule of law and, therefore, the core duties referred to above.

Conversely, if a decision was made that arguing the Chinese government’s point of view would undermine the rule of law, then would that have an impact on access to, and the administration of, justice? Lawyers should not be identified with the views of their clients. Everyone has a right to representation, by limiting those options and withholding services, that could arguably be restricting access to justice and could still be a breach of C28.

While many barristers do things that lay people find to be morally repugnant, such as represent rapists, murderers or terrorists, they do so because they believe in the English legal system and the constitutional principles on which it is run. When you remove that belief and the certainty of the ‘cab-rank’ rule, and you are faced with a choice of whether to represent a client, who a reasonable person may say has questionable views and practices, do the rules and duties just become guidelines to be weighed against each other to find the most ethical path? In those limited circumstances, that appears to be the case.

It is difficult to criticise either Rose and Perry for taking their respective cases, when many UK judges are still eligible to sit in the Hong Kong Court of Appeal, and regularly do so. This list includes the current President of the Supreme Court, Lord Reed.

Conclusion

It is apparent that the cab-rank rule is a vital cog in the administration of justice, but it must be read alongside barristers’ other ethical rules and duties. If the ‘cab-rank’ rule does not apply, then a barrister does not have to accept the instructions. However, all barristers must weigh up other ethical considerations before accepting or declining new instructions. Failure to accept may mean that you are unlawfully discriminating against the prospective client and limiting access to justice. Nevertheless, accepting instructions in some cases, may undermine the rule of law and breach further ethical duties.

Benjamin Ramsey is a first class law graduate from Northumbria University. He completed the BPTC as part of his degree and was called to the bar in 2018. He currently works as a county court advocate for LPC Law, and is actively seeking pupillage.

Please bear in mind that the authors of many Legal Cheek Journal pieces are at the beginning of their career. We'd be grateful if you could keep your comments constructive.