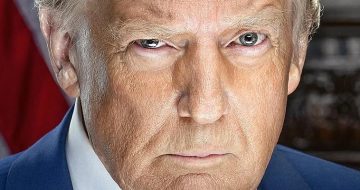

As legal challenges mount, US President escalates his attack on law firms

In just the first seven weeks of his presidency, the Trump Administration faced an astonishing 119 legal challenges — an average of two per day, according to data from Just Security, a journal of the Reiss Center on Law and Security at NYU School of Law, which is tracking the litigation.

Since coming to office, President Trump has ordered a swathe of headline-grabbing actions, such as revoking birth right citizenship for children of undocumented immigrants, dismantling the foreign assistance agency, USAID, renaming the Gulf of Mexico, and banning diversity and inclusion initiatives anywhere in government.

Now these unprecedented executive orders are being legally challenged — almost as quickly as they are being issued – by advocacy groups, associations, trades union and other parties. A number of courts across the states are having to grapple with the legality of Trump’s orders: whether they go beyond what the statutes say, whether they may be unconstitutional. Though previous administrations have also seen their orders challenged in the courts, the extent of the current litigation matches the radical nature of Trump’s orders.

Many of these cases will — eventually — be decided against the Administration and will reverse the executive orders, say experts. Professor Steve Vladeck is the author of the successful One First newsletter as well as a law professor at Georgetown University Law Center in Washington, DC. He tells Legal Cheek:

“Executive power doesn’t override statute and many of the areas that Trump is cutting through have statutory rules.”

But even if he loses in court, Trump is: “Already winning,” says Vladeck. “Tens of thousands of employees have been sent home, organisations have lost their funding, we have witnessed the chilling effect on DEI. So the orders will get reversed in two or three years, but in the meantime, he has created chaos.”

The question that has been swirling around legal circles is: when a court finds against Trump, would he ever dare to disobey? Certainly, the Administration gives the impression that it would. In one case recently, where a judge temporarily blocked the actions of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), Vice-president, JD Vance, bit back on X/Twitter: “Judges aren’t allowed to control the executive’s legitimate power.”

But Vance, who attended, super-prestigious Yale Law School (which he described as “nerd Hollywood” in his infamous book, Hillbilly Elegy), presumably knows this is disingenuous. Judges may not control the executive but they do get to determine what is a legitimate power and what isn’t and that could amount to the same thing.

Vladeck’s hunch is Trump wouldn’t directly flout a ruling: “At some point, when he needs the budget to get through, the President will have to rely on Congressional Republicans to make that happen. I sense that disobeying a court order would be a red line for them. So Trump won’t want to test that.”

Trump appears to have an uneasy relationship with the courts and lawyers right now. At the same time as these challenges are bubbling up in various states, he has taken aggressive steps against law firms. He has issued executive orders directly against two of the US’s largest outfits which have been involved in matters in opposition to Trump.

In February, an order came out against Covington & Burling suspending security clearance for lawyers at the firm (a lawyer there had acted pro bono in the former criminal cases against Trump) and, just last week, Trump issued an even wider order against Perkins Coie for its “dishonest and dangerous activity” that has “affected the country for decades” as the order put it (the firm at one point represented Trump’s former opponent, Hillary Clinton.)

There’s more. In the same order against Perkins Coie, the Administration has extended the clampdown on diversity and inclusion initiatives to law firms as reported in Legal Cheek this week. And the penalties are not trivial: the firms risk the termination of government contracts.

Law firms may experience the chilling effect in other ways, such as being reluctant to hire former government lawyers who have been ousted by the Administration (as part of the dramatic cull in personnel in recent weeks) over concerns that the firms will be tainted by association. Vladeck is optimistic about this, however: “Some firms may want to avoid hiring anyone who has spoken out. But it’s possible that for other firms it may be a win!”

What is more troubling, Vladeck argues, is the damage to the reputation of the civil service in the eyes of younger lawyers and students: “For as long as we have had a civil service, its aim has been non-partisan. And that feels under threat now. Will you see good people go into government in the future given what’s just happened?”