Ethics takes centre stage at IBA conference in Paris

Do you need to be a good person if you want to be a good lawyer? This question formed part of wider discussion around ethics at this week’s International Bar Association (IBA) conference.

Delegates at the IBA, held near La Défense, Paris’s main business district, were encouraged to “stay idealistic” and “help make the world a better place”.

Patricia Sendino, a lawyer who works for BNP Paribas, the French bank, summed up by saying: “You cannot be a good lawyer if you are not a good person.”

If Sendino is right, this begs the question what does being an ethically ‘good’ lawyer mean in practice? Once the profession talked about doing some pro bono work or making sure that you kept your client on the legal path and didn’t turn a blind eye to dodgy dealings.

There is now a debate on whether to take a stand over even who you are acting for.

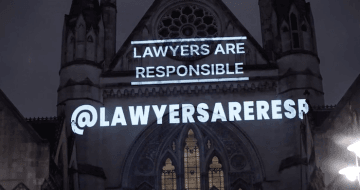

Earlier this year, a group of lawyers, including well-known names such as Jolyon Maugham KC, Professor Leslie Thomas KC and Paul Powlesland, declared in an open letter that they would “withhold [their] services” from fossil fuel companies and would not act in a prosecution of climate protestors. Launched in March, 182 lawyers have now signed the Declaration of Conscience organised through the group, Lawyers are Responsible.

In the US, meanwhile, Law Students for Climate Accountability have put together a scorecard listing law firms that represent fossil fuel companies, with the aim of informing law grads “so that they can make career decisions that are in line with their personal stake in the habitability of our one and only Earth”.

Though there is no exact data on this, it appears that some lawyers are exercising their “climate conscience” in choosing which firms to apply for and what work they will do once they get there.

But should lawyers make these sorts of choices?

For barristers, refusing to act for a particular goes against the longstanding cab rank rule. This rule, referred to by the Bar Council as “the bedrock obligation of an independent referral bar”, prevents barristers from cherry picking clients and ensures that everyone has access to justice.

For the majority of solicitors doing civil work, there is no direct equivalent of the cab bank rule. Whether or not an associate or partner should refuse to work for a particular law firm or, in their job, refuse to work for a particular client, is broadly a matter for individual lawyers and their firms. There are rumours that a few law firms are allowing associates to opt out of working with fossil fuel companies or specific polluters, but this is not published policy.

Passions run high on both sides of the debate about whether lawyers should choose. Lawyers are Responsible say in their declaration: “we express our grave concern that lawyers who support transactions the effects of which are inconsistent with the 1.5c limit contribute towards the consequences [of climate change].”

Strong words indeed.

The counterpoint is that this is mixing up client and lawyer. Brian Archer, president of the Law Society of Northern Ireland, argued at another conference session, that if a lawyer chooses which clients to represent, they are, in effect, playing judge and jury. “I don’t think lawyers should be defined by their clients; that’s a matter for the courts,” he said.

It could also be dangerous — like actors being associated with the parts they play and accosted by members of the public. Archer explained that in Northern Ireland, historically, where lawyers were identified with who they represented: “They could be murdered for that,” he said. “This is serious.”

And some might say that if companies are going to tackle climate change, businesses need advice from good lawyers to make that happen; lawyers working for and within fossil fuel companies could make positive change.

Thus far, the Bar Standards Board confirmed to Legal Cheek that it hasn’t yet had any complaints or referrals where a barrister has refused to act due to the identity of the client. But it may only be a matter of time.

For solicitors, Nick Emmerson, the new president of the Law Society (which published guidance on the topic in April), speaking at the conference, argued that law firms should accommodate an expression of “climate conscience”. “There is scope for law firms to enable lawyers to not work for a particular client or matter,” Emmerson explained. “It’s the same issue that came up with tobacco companies previously.”

Perhaps what is needed is greater engagement between firms and their lawyers about what are their shared values, and, equally importantly, how to afford those values when faced with the commercial realities of running a firm. Speaking to Legal Cheek, one managing partner of a law firm in Nigeria, Babatunde Ajibade, said: “A law firm is a collective body making decisions as a group. If that collective has decided to take on a client, then l would hope that the lawyers working at the firm would stand by that.”

The IBA’s annual conference concludes today (3 November).