Meet the mad and murderous Dineley Gooderes

The prize for history’s worst family feud is undoubtedly hard to judge. But the breakdown of the marriage between John Dineley Goodere and Mary Lawford in the eighteenth century and the subsequent demise of the Goodere Dineleys is surely in the running.

The fateful tragedy started back in 1717. Following the death of his older brother, the second eldest son of the Dineley Goodere family, John, was forced to give up his life as a merchant marine in India and later a volunteer on HMS Diamond in war against France and take over the family estates. This meant by the age of 33 he had control over the large family house on the Dineley side and 1,600 acres of land from the Goodere side.

That year John decided to expand his wealth by marrying Mary Lawford, a 14-year-old with a valuable estate and inheritance lined up. By 1726, John looked like he was in an extremely strong position with an income of £4,800 (worth around £665,000 in today) per year and three houses.

However, he appears to have suffered from a hereditary mental instability, a terrible temper and a potent vindictiveness. The fact that he groundlessly imprisoned and ordered to be beaten a woman who had testified in support of his cousin in an earlier family lawsuit and needlessly carried out the last ever trial by ordeal on record in English history in an attempt to root out a suspected witch is more than a little hint of what he was capable of. Such acts saw his membership of the House of Lords revoked just four years after he was made a peer.

It is therefore unsurprising that he did not respond well to strains in his marriage. Nor was his relationship helped by the fact that both he and his wife Mary were drunkards. After several violent arguments (John abusively chained up Mary on two occasions: for 36 hours following his wife’s jealously over John’s alleged closeness with one of their female servants in 1726 and for several days following Mary’s attempted elopement with Sir Robert Jason in 1730), the pair took their fight to the courts.

This is where the family was to be plunged into a legal nightmare that was to destroy their fortune. Both used the courts to try and bankrupt one another. After John went back on a private separation agreement, he deliberately tried to run up Mary’s legal costs which resulted in her being imprisoned for a short time. Mary, who was a spendthrift, retorted by enforcing the separation agreement John had broken. She then encouraged her creditors to pursue John with lawsuits for the payment of her debts as per the agreement.

In the ecclesiastical courts, Mary unsuccessfully sued John for cruelty, failing to meet the very high required threshold, whilst John unsuccessfully sued Mary for adultery with the case collapsing as it emerged that John had bribed a witness. John, however, was awarded £1,000 (around £172,000) in damages against Sir Robert Jason and in 1737 he succeeded in having Mary sent to prison for conspiring to accuse him of attempted murder for one year, a period of time that was extended when Mary was confined in a sponging-house, where defaulting debtors were held so that they could arrange their affairs with their creditors. Whilst she was there, she continued deliberately racking up more debts.

John then failed to obtain a divorce from parliament, the only method available back then. This would have relieved him of Mary’s debts from the date of her first conviction for adultery in 1730. Nine years later, however, they remained married, ruinously in debt and with a legal bill of around £14,000 (roughly £2.2 million).

Amongst other things, this story is an example of how parties could use the law without being motivated by any desire for justice, but rather as “a means of waging war, of obtaining revenge, and of finally destroying an enemy”, a point powerfully made in the historian Lawrence Stone’s magisterial retelling of the Dinely’s litigation.

This remains an issue today. Sir Andrew McFarlane, head of family courts in England and Wales, recently reiterated how although “the law provides a structure… to resolve the dispute […] in the end, it is not a legal issue, it’s a relationship problem”.

“My feeling is that about 20% of the families who come to court to have a dispute about their children resolved, would be better served by at least, first of all trying to sort it out themselves in other ways,” Sir Andrew McFarlane told the BBC. So what are the solutions?

The advent of no-fault divorce, where either or both spouses need only file for a divorce rather than being forced to give one of five possible reasons (adultery, unreasonable behaviour, desertion, two years separation (if both agree), or five years separation (if only one person wants the divorce)), has been broadly welcomed following the widely felt injustice in Owens v Owens.

But some still think that the new 26-week time period starting with a ’20-week reflection period’ on giving notice is too long. More generally, Sir Andrew is concerned about the effect a lengthy process can have on children and is trialling child impact assessments to give parents “a wake up […] as to the impact of what they are doing on their child”. Other ideas include ensuring that the process of separating finances and obtaining consent orders are simple to understand and as uninflammatory as possible.

But there remains a practice (especially for wealthy couples) of warring spouses like John and Mary racking up costs and jurisdiction shopping. England and Wales is known for being more generous jurisdiction for the financially weaker party, whereas Spain and France for example are less so.

As Lawrence Stone points out, divorce has always meant different things for different groups within society and without any “sequence of unambiguous moral improvements which all lead towards the greater happiness of the greatest number”. According to Stone’s analysis of divorce from 1530 to 1987, change seems to come in fits and starts as it faces new fashions, changing moral values and those groups (including lawyers!) with great incentives to preserve the old system.

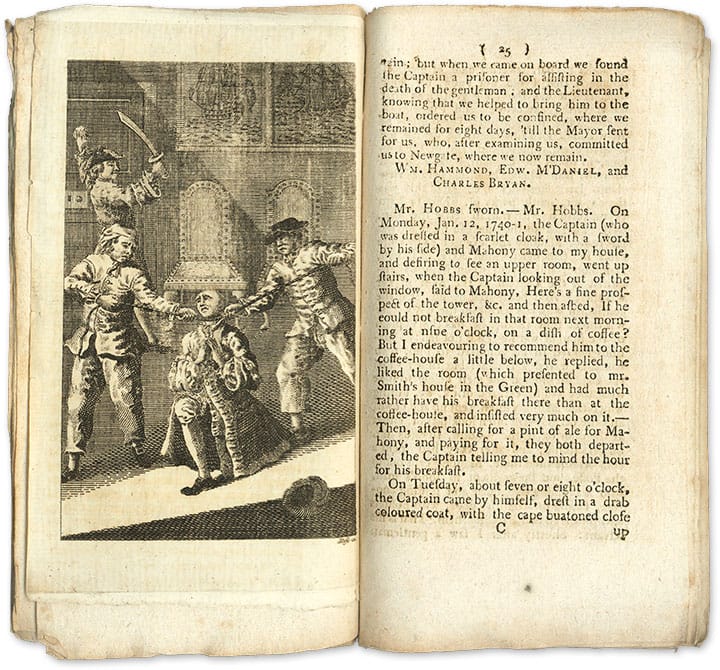

The likes of John Dineley Goodere are known to blame the system and the greed of the lawyers who run it. Having failed to obtain a divorce from parliament, John had incited a new level of rage from his younger brother Samuel. Upon discovering his father’s will only gave him a life interest in his father’s properties with everything passing to Samuel and his heirs after John’s death, John managed to use his estranged son, who died from ill-health and neglect two days after John had obtained the necessary signature to cut his off brother from the will. In 1741, Samuel retorted by kidnapping and having him killed on a ship in Bristol. Samuel was then found out and hung later that year.

Whilst taking him to the boat, Samuel said to John of his divorce: “Have you not given the rogues of lawyers money enough already? Do you want to give them more? I will take care that they shall never have any more of you; now I’ll take care of you.”

But it is clear that lawyers were certainly not the main cause of the problem here. This is put beyond doubt by the fact that Samuel had abused the good faith of his Bristol lawyer Jarret Smith by getting him to organise a reconciliatory meeting to put an end to their strained relationship that had also been the subject of litigation. Lawyers were just a means to an end for this feuding family. The same point may be generally observed as a challenge for divorce law reforms. Lawyers should continue to advocate changes and more options and support must be made available, but ultimately it is up to partners and spouses to play along.

Will Holmes is reporter at Legal Cheek and a future trainee solicitor at a magic circle law firm.