Will Holmes explains how revisiting medieval debates on natural law could improve the application of modern human rights

The Middle Ages, sometimes referred to as the ‘Dark Ages’, are not popularly perceived as a great time for the rule of law, or, for that matter, human rights. But medieval law holds an interesting lesson for the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), especially in relation to one of its more controversial developments: positive obligations.

In medieval times, tension existed between four different types of laws: natural, divine, customary and positive. What do these all mean? Natural law refers to a set of moral values that are intrinsic to human nature, whilst customary law describes particular traditions and norms observed by communities. Divine law was law derived from God, whereas positive law was law made by kings and political institutions.

Natural, divine and customary law often stood in opposition to the King’s authority. Political theorists at the time make clear that positive law was the lowest in the pecking order. Thomas Aquinas noted that an unjust positive law was “no law at all”, whilst John of Paris and Jean Bodin, despite over two centuries passing between the two and significant differences regarding their perspectives on sovereignty, both believed the sovereign authority to create positive law was derived from natural and divine law.

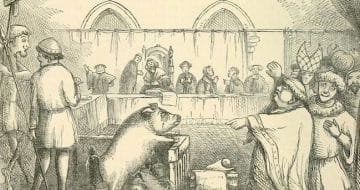

The practical effects of this were clear. John of Paris extrapolated that the King was akin to the head of a medieval corporation (a group of individuals in a community that functions as a collective organisation) who its members could remove if that head of the corporation had failed to respect any of these three sources of law or the corporations constitution. In line with this corporate theory, in Germanic customary law there emerged a “right of resistance” for the breach of the king’s primary duty: protecting the law.

Indeed, the likes of Pepin the Short and Louis the Stammerer were known to swear oaths to obey the law (perhaps through gritted teeth) and stronger kings such as Henry IV could not avoid respecting papal decrees (to his annoyance). In short, the historian R. W. Carlyle concludes, “the principle foundation on which medieval political theory was built was the principle of the supremacy of law”.

This strikes a chord with some interpretations of the ECHR’s purpose which has on occasion been known to achieve a similar goal. Take, for example, the judgment of Giovanni Bonello in the case Al-Skeini v UK, where he proclaimed that the Contracting parties to the international treaty that came into force in 1953 “strove to achieve […] the supremacy of the rule of law” and therefore the ECHR should be interpreted with such intentions in mind. But this article does not aim to vindicate the likes of Bonello. Quite the opposite, it offers an alternative direction for the ECHR based on a more complete examination of the foundation on which modern human rights was constructed: natural law.

The strand of medieval natural law that has been preserved today is natural rights. This stems from one side of a medieval debate about whether something that was permitted in law meant that that individual had a right to it. Natural rights proponents suggested that this right existed independent of state action and therefore the state had an obligation to allow an eligible individual to pursue that right.

The legacy of this way of thinking has created excessive tension between states and human rights legislation. This can be clearly observed in the rise of certain far-reaching positive obligations — a requirement for the state to act in some way, as opposed to refrain from acting – being imposed on ECHR Contracting states that have attracted some criticism from academics and judges alike. These can be quite expansive as Lord Sumption has pointed out in relation to Article 8 and have been widely criticised in relation to the extra-territorial expansion of the treaty beyond the territories of its signatories. This harshness of this position has even led some to advocate leaving the ECHR.

However, a more nuanced perspective has recently been unearthed by Brian Tierney in the form of ‘permissive natural law’. ‘Permissive’ here refers to “a realm of human free choice” that favours a less imposing top-down approach to rights enforcement and created a practical space for mutual consideration and compromise. These rights were instead, as is well summarised here, “rooted in respect for the person and the community and committed to the flourishing of both within the confines of prudence and public peace”. Although a legal right, the practical effect was dependent on social conditions.

To give one example, medieval Canon law granted individuals in need of food a right to sustenance that could be claimed against a rich man. But unlike socio-economic rights today, this socio-economic right was not at all controversial as it was only valid in consideration of the rich man’s right to property and the state or local community’s capacity. In short, it was less absolute and avoided rights growing beyond the institutions that could uphold them (what appears to me to be the primary concern in relation to modern human rights today).

The matrix of tension between natural, divine, customary and positive law that defined the rule of law in the medieval period set the stage for the key tensions in modern human rights law. The demise of medieval divine and natural law in the face of the Reformation and the Enlightenment came as rulers increasingly used governments of experts to expand their activities in response to particular practical needs of the community, strengthening the reliance on positive law. As the state expanded yet further, Tamanaha notes, so did communities, weakening the effectiveness of customary law. Positive laws strength seemed to demand a strong counterbalance.

After positive law had had its day, with the doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings marking its apex, natural law was vigorously revived after being confined to a “recondite area of Roman Catholic thought”, in the words of Tierney. But the nuance of the medieval debate about when permissions could become rights and how it was best to enforce those rights was lost to history. As the UK government, laden with debt and facing recession, reconsiders the unquestionable importance of the ECHR, the more practical and localised other half of natural law has never been more in need of revival.

Will Holmes is reporter at Legal Cheek and a future trainee solicitor at a magic circle law firm.