Future magic circle trainee William Holmes examines the interplay between justice and entertainment

Justice has long been a spectacle.

Today, battling barristers, curious cases, shamed celebrities and unpredictable judgments make the perfect recipe for TV gold. The courtroom is a stage for the likes of Court TV to turn legal procedure into a spectator sport. But back in Anglo-Norman England, it wasn’t so much Court TV’s famous catchphrase ‘gavel to gavel’ as it was ‘wooden club to wooden club’.

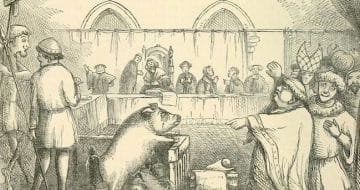

In Anglo-Norman land disputes, lawyers would pick up their baculi cornuti (small wooden sticks), strap on a limited amount of protective gear and let their clubs smash out some justice. Trials by battle meant that these medieval ‘lawyers’ — known as champions — were valued primarily on their physicality. William of Copeland was the top-ranked land disputes champion of his time. One commentator praises him highly, noting that the mere sight of him is enough “to scare any tenant [defendant] who might have considered countering his challenge”.

Unsurprisingly, trials by battle were a popular spectacle. And fight-night-style trials were not the only type of performative justice. One that might appeal to fans of shows like Man vs Food and The Great British Bake Off are trials by cake. This was where individuals would seek to prove their innocence by eating a dry piece of consecrated bread. If you could swallow it, you were deemed to be innocent. But if you choked, you were guilty.

In 1053, Godwin, Earl of Kent, famously was said to have failed this test. He had sworn that he had no involvement in the assassination of the King’s brother. The bread, however, thought otherwise and Godwin choked to death. The prominence of trial by cake meant that the spectacle even had its own catchphrases like “May this morsel be my last!”. It’s not quite “soggy bottoms”, but it reinforces the evidence that these trials were, at heart, performances of justice.

I am sure Court TV would be keen to revive some of these eye-catching legal traditions. But I am less sure that the broadcasters would be mindful of their role in the passage of justice. These dramatic trials (in their many forms) were deliberately designed to be spectacles and were closely tied with legal procedure for a variety of reasons.

For many, these trials were a way of appeasing public dissatisfaction created by an inconclusive legal process. Both trial by battle and trial by cake were solutions in cases where there was not sufficient evidence for a judge to come to a decision. With such uncertainty, society looked to God to make the final judgement. These unusual tests provided a definitive answer to seemingly unsolvable legal questions because God was thought to intervene in the name of justice to defend the innocent. In essence, the trials meant nobody could escape the law thanks to a lack of evidence.

Whilst these superstitions may have been of driving force behind some proceedings, trial by battle seems a bit different. In fact, these traditions had secular origins and normally did not possess the cathartic closure of seeing the guilty party dead at the end of the proceedings. The champions could submit to an opponent by shouting the word “craven”. This meant that death was a rare outcome. Rather, there appears to be an economic rationale behind trials by battle: judges made money from the fights.

Although litigants were often incentivised to settle due to the cost of hiring a professional champion and the unpredictability of the outcome, effort was made to lower the barriers-to-entry by excluding expensive requirements such as horses, swords and armour. Judges were also masters of the pre-fight hype. They frequently whipped up spectators by making the champions swing a few punches “for the sport… and the public”, especially when the litigating parties disappointed the crowds by settling at the last minute. Just like Court TV, judges looked to profit from legal drama as much as possible.

Want to write for the Legal Cheek Journal?

Find out moreThe inventors of courtroom drama, however, were the ancient Greeks. This was in large part due to the fact that legal procedure was democratised. In Athens, all cases would be decided by a large jury (typically of around 501 jurors) which consisted of Athenian citizens over the age of 30. There was no judge or legal expert to guide them on the technicalities. Grieving friends and family members would be wheeled out onto the stage to appeal to jurors’ emotions. Sex and violence were also recorded by some writers as methods used to sway juries. The extent to which this really happened, however, is questionable. But it is clear that discussion of such dramatic performances in court were considered plausible.

Contemporary accounts tell us that ancient Greek trials fell into three genres that echo Greek theatre: tragedy, comedy and highly rhetorical cross-examination. In line with these links to the theatrical, defendants were often happy to try their hand at acting. In 489 BC, an injured defendant called Miltiades lay in total silence on a stretcher in front of the jury throughout the proceedings, replicating the pose of a dying tragic hero that was a common trope in Greek theatre. Lawyers also employed deliberately dramatic devices. A good example of this was when the poet Cratinus had been accused by his enemies of killing a female slave girl. It was only after 14 witnesses had testified that Cratinus had murdered her, when he finally revealed the very much alive slave girl in question to the shock of the jurors.

The proliferation of courtroom drama came in response to the democratisation of justice. No judge with legal experience was present to clarify the letter of the law. Instead, the people had the final say. And they enjoyed a show. Consequently, trials were more often than not the arena for vexatious cases that are reminiscent of the presidential and election debates we have today. From smearing political opposition to getting personal revenge on an enemy or rival, ancient Greek trials were a space to score political points and make or break reputations.

So, have any of these performative traditions survived today?

Scholars have extensively analysed traditions related to movement, space, gestures and clothing in the courtroom. They reveal a theatrical choreography behind legal proceedings, some elements of which have worrying consequences. For example, one study found that “jurors may be more likely to convict a person sitting in a dock than if the person were sitting at the bar table” — a threat to the presumption of innocence.

So, why do our courts function in a performative way? Trials seek to establish a convincing truth. By attempting to fill the gap between the truth and the “legal truth” that is represented during a trial, courtrooms are a space for disputed stories to be stitched back together. Lawyers propose and poke holes in competing narratives. Judges and juries decide which they are most convinced by in relation to certain legal issues.

This means the modern trial is dramatic by virtue of its narrative function. The late associate justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court, John E. Simonett, went as far as to compare the criminal trial to a play. He explained, a trial “has a protagonist, an antagonist, a proscenium and an audience, a story to be told and a problem to be resolved, all usually in three acts”. But, the extent to which we permit this dramatisation of justice is in our control.

So, what do the popularity of Court TV and the British government’s decision to allow a judge passing a sentence to be filmed and broadcasted publicly tell us?

Unlike in ancient Greece or Anglo-Norman England, throughout Europe today, we tend to prefer that the law is decided by a few legal experts. The push for TV trials indicates a move in a different direction. It both democratises and dramatises justice. This is not necessarily a bad thing. But history gives us some examples of when this happened that are worth considering. Athenian trials moved justice further away from the legal and towards the vexatious. Trials by battle and trials by cake used the spectacle of justice to an economic or social end. TV trials force us to reconsider where we want our justice system to be on this democratic and dramatic scale. The cameras are really asking us: what sort of justice do you want?

William Holmes is a penultimate year student at the University of Bristol studying French, Spanish and Italian. He has a training contract offer with a magic circle law firm.

Please bear in mind that the authors of many Legal Cheek Journal pieces are at the beginning of their career. We'd be grateful if you could keep your comments constructive.