Future magic circle trainee William Holmes unlocks the method in ‘Mediaeval madness’

In Mediaeval times, animal trials were far from a trivial matter.

At great expense to the state, animals were held in custody before trial and provided with a state-funded defence counsel. Animal defence lawyers had long hours and challenging cases. And for some, it was even the ticket to the top. The French lawyer Bartholomew Chassenée’s defence of the rats of Autun in 1522 brought him such great renown that he ended up in a position equivalent to the role of Chief Justice.

But why were animals treated in this way by the law? Then, animals had certain rights and duties restricted and others maintained. This led to Mediaeval animal’s curious status as partial legal persons. They could be subject to criminal and civil prosecutions but were still property by law. This allowed the legal system to respond to any harms caused by the animals, whilst still allowing their owners to use the animals for their economic benefit.

Today, new technology, such as the artificial intelligence (AI) “creativity” machine DABUS, has developed the ability to act autonomously. Despite this, AI technology is not a legal person (bar the exception of the AI-humanoid Sophia’s Saudi Arabian citizenship). If AI can independently cause harm, like the Mediaeval animals, surely it should be able to face criminal and civil charges for its actions?

So, does AI require some form of legal personhood? And, if so, what is the best model for this? Does the Mediaeval model of partial legal personhood for animals provide a helpful template?

Inventors inventing inventors

In October 2018, the physicist and engineer Dr Stephen Thaler filed UK, US and EU patents for two new inventions: the neural flame and the fractal container. However, both of these inventions were not created by Thaler, but his AI “creativity” machine DABUS. In these patent applications, Thaler named DABUS as the inventor, but himself as the owner of the patents.

Thaler’s patent applications ask two questions: “can a machine be an inventor?” and, if so, “who owns the patents?”. In response to the first question, the UK Intellectual Property Office’s (IPO) Hearing Officer reasoned, “I have found that DABUS is not a person… and so cannot be considered an inventor”, whilst the European Patent Office (EPO) explained “an inventor has to be a human being, not a machine”. This is due to a lack of clarity in the law on who can be an inventor.

The second question (“who owns the patents?”), however, highlights how AI’s absence of legal personhood is even more fundamentally problematic. At the moment, inventorship is legally coupled with ownership. By default, the inventor is the owner of the patent unless it is assigned to another entity. But because DABUS is not a legal person, it cannot own or assign ownership of the patents to anyone.

Accordingly, as noted by the UK IPO, Thaler “is still not entitled to apply for a patent simply by virtue of ownership of DABUS, because a satisfactory derivation of right has not been provided”. The key to resolving the conflict between inventorship and ownership, in DABUS’s case, is to define the machine’s rights and duties.

Method in Mediaeval madness

In this scenario, the Mediaeval model of partial legal personhood offers a practical solution. It uncouples the rights and duties of a non-human entity to allow DABUS to have partial legal personhood, but still be property.

It is clear that granting AI the full status of a legal person would be undesirable for those who work to create technology like DABUS. Developing this sort of technology is complicated and expensive. If autonomous AI was granted full legal personality, entrepreneurs hoping to develop commercial versions of this technology could no longer own their inventions.

Want to write for the Legal Cheek Journal?

Find out moreFurthermore, the deincentivisation of the development of AI technology might not only be detrimental to entrepreneurs. If academics’ claims that “powerful AI systems could hold the key to some of the mega challenges facing humanity — from the cure for cancer to workable solutions for reversing climate change” prove to be true, the underdevelopment of AI could be detrimental to society too.

Crime without punishment

At the same time, the Mediaeval model of partial legal personhood intends to install liabilities on its non-human entities. This means that DABUS, rather than Thaler, would face civil or even criminal prosecution for his machine’s inventions. Surely any harm caused by the neural flame or the fractal container could not be considered Thaler’s fault since he did not create the inventions?

However, incorporating non-human entities for the purpose of liability begs the question of how to satisfactorily punish autonomous non-humans. Today, the only legal entities that do not have people behind them such as the Whanganui, Ganga and Yumuna Rivers, Lake Erie and Ecuadorian ecosystems were not intended to make them liable for lawsuits. Instead, legal personhood gives these entities enforceable rights for the purpose of their ecological protection. With other non-human legal entities, such as corporations, this is not such a problem. The law can look behind the artificial entity to the humans responsible using the legal remedy called ‘veil-piercing’. This is not without its own faults, but it largely resolves the issue of using non-human entities as shield from the law.

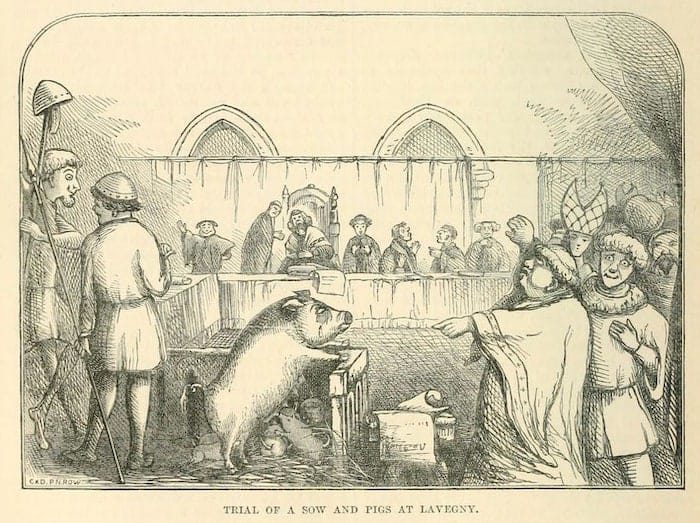

Mediaeval animal trials had a human-like flexibility regarding criminal sentencing. A case where a man was accused of sexually assaulting a donkey was brought to court in 1750. The donkey was spared as “she had not participated in her master’s crimes of her own free will” — similar to the principle of consent. Accordingly, the man responsible for the sexual assault was sentenced to death. In 1457, a sow was sentenced to death for killing a five-year-old. However, her five piglets, who were party to the same crime, were spared on account of their immaturity — a similar principle to juvenile sentencing.

Currently, such human-like criminal sentencing feels both inappropriate and unsatisfactory and is therefore highly problematic for AI’s status as a legal person. But it is not impossible. A system of legal sentencing for autonomous robots may become clearer when such technology is more deeply embedded in our societies.

That’s just how we do things

Many have questioned why Mediaeval societies held such unpractical animal trials. Some have concluded that these trials were just a part of religiously-motivated, “superstitious and ritualistic” Mediaeval madness. But others attribute the unusual trials to cultural norms.

The great cost, effort, and, as Chassenée’s success proves, legal rigour around the animal trials suggest that this was more than just entertaining theatre. It is clear that animals were more culturally embedded in the preindustrial agrarian Mediaeval society than today. Farming account books suggest that farmers in the seventeenth century spent up to 16 hours a day with animals. This may have increased the likelihood that people could derive a sense of justice or injustice for animal cases which is reflected in some of the judgments.

In the UK today, urbanisation and the widespread rise of factory farms and mega farms has led to a different sentiment towards animals. It is, perhaps, therefore unsurprising that animals no longer enjoy the right to be defended before a court. Moreover, these Mediaeval trials are reflected in our culture as a form of show trial entertainment in the BBC film (starring Colin Firth) The Hour of the Pig, which is based on Chassenée’s career.

Culture and politics play a large role in deciding legal personhood, which is often a mere reflection of prominent social sentiments. This may explain why culturally important rivers, environmentally important rivers and ecosystems, and certain religious texts are the latest non-human entities to join the legal persons club. The hardwiring of technology into society may have a similar social effect. But for now, this remains the realm of imagination such as is envisioned in the Oscar-winning film Her.

Conclusion

Legal personhood is defined in relation to humanity. Non-human legal entities inevitably complicate this. But it would be a mistake to ignore the potential harms that can be caused by non-human entities, due to stubborn attachment to a very human law. In the case of DABUS, the Mediaeval model offers a solution. But most importantly, it underlines how culture often precedes practicality. Mediaeval animal trials provide an example of where it seems that a society critically engaged in determining what rights and duties would be appropriate for their animals. AI machines like DABUS may continue to make such practical debates prevalent, so our society can evaluate the most desirable form legal personhood (if necessary) for AI.

William Holmes is a penultimate year student at the University of Bristol studying French, Spanish and Italian. He has a training contract offer with a magic circle law firm.

Please bear in mind that the authors of many Legal Cheek Journal pieces are at the beginning of their career. We'd be grateful if you could keep your comments constructive.