But Agatha Christie’s Witness for the Prosecution grandeur is a world away from the realities of the criminal justice system

Moments before being whisked away by policemen for a murder he swears he didn’t commit, Leonard Vole booms: “This is England — you don’t get convicted for things you haven’t done.”

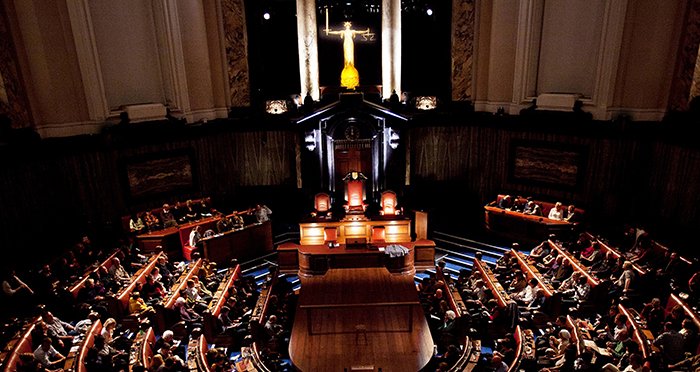

Witness for the Prosecution, a gripping whodunnit by Agatha Christie, has the pursuit of justice at its heart. Based on her short story from 1925, the play is currently being performed in the novel surroundings of the Council Chamber of London’s iconic County Hall. It’s very, very grand.

Main character Leonard has been arrested and charged with murdering Emily French, a woman twice his age he befriended by accident. The victim, 56, was found dead in her home which she shared with her housekeeper and her eight cats, killed by a blow to the head.

The evidence against him “couldn’t be more unfortunate”, his barrister admits: the murder takes place just days after the dead woman altered her will to leave Leonard her sizeable fortune. Yet, Leonard is charming, a chirpy young car enthusiast who has fallen on hard times and who you can’t help but side with. Perhaps his defence barrister’s assistant, Greta, puts it more succinctly: “He’s far too nice, and he’s such a dish.”

Agatha Christie’s trial-based crime thriller, while entertaining us with piercing cross-examinations and lawyers going head-to-head, gives us a glimpse into the world of miscarriages of justice. Any law student with a case summary of the Guildford Four or Birmingham Six at their fingertips will appreciate this. Netflix series such as Making a Murderer and The Confession Tapes have seen a wider audience cast doubt on the criminal justice system’s truth-seeking clout.

Christie is definitely having a moment right now with a number of film and TV adaptations, including last year a US version of Murder on the Orient Express starring top-name actors like Judi Dench and Johnny Depp. The Witness for the Prosecution production is without bells and whistles: throughout the two-and-a-half hours (with a 20-minute interval) the actors remain in the same clothes. Locations, of which there are three, are denoted by actors moving furniture on and off the stage.

But what Witness for the Prosecution lacks in gaudy theatrics it makes up for in rich courtroom drama. The shadowy-faced judge’s piercing eyes; the audible gasps from the audience in (surprisingly big and comfy) seats as the play reached its climax; the chatter in the interval toilet queue about whether Leonard did it or not — moments like these make criminal law seem so glamorous, really.

We know it’s not. The grandiose County Hall on the Thames, once the headquarters of the capital’s own government, looks nothing like a more typical, haggard crown court building of today.

Wilfred, Leonard’s barrister, has a number of leisurely chats with his client, even before he’s arrested; they are a far cry from the dropped-on-your-desk-the-night-before-trial cases criminal barristers too often complain about. I wonder what Wilfred, suited and booted and sharing a stiff drink with the instructing solicitor, John, in his cleanly-furnished office, would make of today’s courts: as a result of legal aid cuts protests, murder suspects are appearing without barristers because 100 chambers are refusing new work.

So: don’t use Witness for the Prosecution as ammunition for a career in law. Take it for the fictitious delight it is, and you’re in for a treat.