‘Fed up of having to pay to work’

It’s no secret that life at the criminal bar is hard. Often relying on legal aid funded work, many barristers find themselves working long hours on distressing cases with little compensation at the end of it all.

These problems are only made worse, a top junior barrister has warned, by the exodus of barristers, leaving more poorly-paid work behind and piling the pressure on those already struggling.

Writing recently for Counsel magazine, Joanna Hardy-Susskind, junior barrister at Red Lion Chambers, has offered a harrowing insight into why people are flocking to different areas of practice, and the impact that this is having on the criminal bar.

Conducting her own form of exit interviews, Hardy-Susskind spoke to a number of anonymous colleagues who had left, were tempted to leave, or had diversified their practices in recent years.

The first issue? Pay. Barristers who spoke to Hardy-Susskind spoke of “working for free”, tackling work at a “shocking rate”, and trying to manage a “culture” of doing extra work for no pay. One went as far to say that they were “fed up of having to pay to work”, with others struggling to keep on top of mortgages and childcare.

One more senior barrister noted that the compensation for work and respect for criminal barristers had “dwindled”, and with the working conditions deteriorating they “started to dread getting up in the morning”.

Those who have been following the issues at the criminal bar for a while will remember the strikes that took place in 2022 that only came to an end when barristers narrowly voted in favour of a 15% pay rise for legal aid work.

On top of the poor pay other interviewees cited the distressing nature of work. “Back-to-back” sexual offence trials that are both “physically and emotionally gruelling” were a particular target for criticism, especially in the absence of fair pay. Others said they were simply tired of being the “public face of a crumbling system”.

A particular issue with the chaotic and unscheduled nature of the criminal bar is caring and familial responsibilities. Fathers Hardy-Susskind spoke to felt they were “physically or figuratively” absent from families, with the work they were doing “isolated and insular”.

Mothers also had great difficulty navigating a return to work, with one person commenting that, when she attended chambers to collect some paperwork with her baby, she was welcomed with a scolding of “I had not realised this was a nursery.” When looking to a more senior barrister for help she was asked “where is the father in all of this?”

“I am at a stage in my life where I want to have a family…,” another barrister commented, “and partly I feel like with this job I am not sure how I would ever manage to have a child and actually be there to raise my child.”

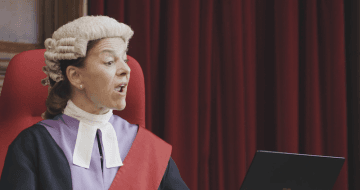

The “final straw” for others was their treatment by judges. One junior recounted being publicly berated by a judge for now knowing where his opponent was. “That was a moment of clarity, I realised how ridiculous the criminal justice system was, how petty, how backward, and how unhealthy.”

Wrapping up her expose, Hardy-Susskind added that:

“We have been conditioned to sacrifice perfectly normal activities like eating, sleeping and caring for children to keep a very poorly paid show on the road.”

The impact of this exodus of barristers? Back in 2019 there were 71 cases that could not proceed because of a lack of counsel. Last year this number hit 1,436.