New research shows how judges can fall into psychological traps when making decisions

The famous representation of justice as a woman holding a pair of scales is often wearing a blindfold as well. The idea is that Lady Justice is blind to everything but the law: the personal characteristics of litigants or judges themselves aren’t supposed to come into it.

In reality, as every jobbing lawyer knows, judges are human beings too. Although trained in how to avoid bias in their thinking, those deciding legal cases are unconsciously influenced by non-legal factors all the time.

There’s a growing body of psychological research showing how common this is — some of it pretty mind-boggling.

One recent study looked at the real-world sentencing decisions of judges in the US state of Louisiana. Boffins calculated that juvenile court sentences for Black children aged 10-17 were higher if the popular local football team, the LSU Tigers, had recently lost in an upset.

The study found that surprise losses for the Tigers correlated to a 6% rise in sentences for Black male juveniles (and only them) for up to a week after the game.

Fair enough, bias against Black people in the Deep South isn’t necessarily that surprising. But there are plenty of more subtle examples.

In Sweden, researchers asked criminal judges to pass hypothetical sentences in eight case studies based on real criminal trials. Half were asked to first decide whether the defendant should get bail, and then to decide guilt or innocence. The other half were told whether or not the defendant got bail, and to just decide whether they did the deed or not.

All were more likely to convict those denied bail, but there was a big difference depending on whether the trial judge also made the bail decision. The judges who decided to deny bail themselves were almost three times more likely to pass a guilty verdict than those who were told that the defendant had been denied bail by another judge.

That’s a potential example of what psychologists call “confirmation bias”: people are heavily influenced by preconceived beliefs — in this case, formed by the view that the defendant was dodgy enough to be remanded in custody rather than bailed — even if the evidence points another way.

Cases involving numbers are fertile ground for psychological bias. The phenomenon of “anchoring” is where planting a totally random number in a judge’s head draws them towards that number in calculating, say, a sentence length or compensation amount.

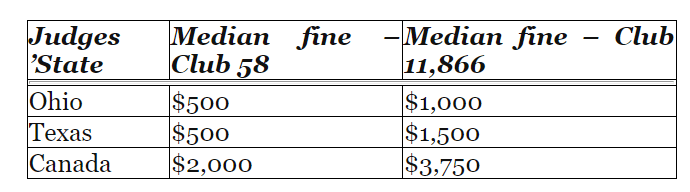

One experiment asked municipal judges from Ohio, Texas and Canada to say how much a hypothetical nightclub should be fined for breaching noise regulations. One group was told the nightclub was called “Club 58”; the other group got “Club 11,866”. The facts were otherwise exactly the same.

Despite that, judges gave much higher fines on average to Club 11,866 than to the identical Club 58. The high number in the name, although totally irrelevant to the task at hand, had nudged them up.

Dr Brian M. Barry from Technological University Dublin has just published a book drawing together the latest experimental research on judicial reasoning.

Writing in How Judges Judge, he says it’s “unnerving” to see just how susceptible those on the bench can be to “cognitive biases, prejudices and error”.

But it can be overcome. The literature also shows that experienced judges are impressively resistant to “hindsight bias”, or thinking that an event or outcome was more predictable than it actually was.

One older study involved American judges being asked to decide whether a train company was legally obliged to carry out certain repairs. One group was told that the company had a perfect safety record; the other group was told there had been a recent accident. Impressively, the two groups were just as likely to decide the case the same way, based on the rules rather than the legally irrelevant event.

Dr Barry says that there are plenty of ways for judges to correct for their human failings once made aware of them.

But in the meantime, it’s no harm for lawyers, students and judges themselves to be aware of how even the most finely tuned judicial brain can be hacked.