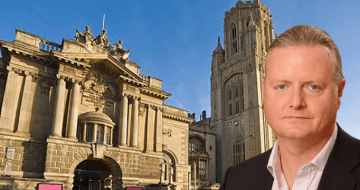

The head of Leicester De Montfort Law School, Professor Kevin Bampton, welcomes the scrapping of the LPC. Ahead of his appearance at LegalEdConNorth on 30 January in Manchester, he explains why

Changes to the route to qualification as a solicitor should force all law schools and potential lawyers to really re-examine the value of legal education and the opportunities it provides. Indeed, in many ways, the end of the Qualifying Law Degree (QLD) and Legal Practice Course (LPC) is the biggest mandate for law schools to show the value of undergraduate and postgraduate/professional study.

Last week the Legal Services Board (LSB) highlighted that there is still more to do before the Solicitors Regulation authority (SRA) gets the final sign off for the Solicitors Qualifying Exam (SQE). This may come as a glimmer of hope to many who might see the SQE as a retrograde step in academic, diversity and quality terms. There may even be sighs of relief for a few heads of law schools for whom the LPC and the QLD are at the core of their business model. However, whatever one may think about the impact of the SQE on the quality of solicitors training, it has certainly stirred up thinking in the academic community.

As the head of one of the UK’s largest law schools with over 2,000 students, I can’t help welcoming any impetus that forces legal education to be judged on its own merits. The SQE has highlighted deficits in the undergraduate curriculum. Principally, these revolve around the absence of the study of procedure, legal consumers, ethics and regulation. This is a defect in the current QLD, not because of its potential impact on employers and employability, but because law is a social reality, not a purely theoretical endeavour. For all my academic career, I have been committed to ensuring that academic students of law understand the psychological, practical and ethical challenges of law as a social reality, either through experiential learning, simulated practice or empirical research.

Think about the study of history. The last century saw the move from historiography, where students studied only what others wrote about the past, to a commitment to primary sources and the contextualisation of historical writing. This fundamentally changed how we understood the past and ourselves. Legal education in many of the UK’s law schools is still focused on the study of academic writings about appellate court written judgments or the judgments of senior judges writing about legal transactions and problems about which they can only ever have second hand knowledge.

While this is invaluable as part of understanding law as institutional knowledge, it is also inadequate as a true study of law as a social reality. The consequence of this is that graduates enter law jobs feeling that their studies are irrelevant and those who continue in academia have a distorted view of law, which they go on to perpetuate. The victim of this is the legal system, which cannot benefits from practitioners who can bring to bear useful higher learning from their studies.Nor does it benefit from useful research beyond what is founded in a focus the minority of appellate court decisions.

Conversely, I would not advocate an approach which tried to slavishly link the study of law to practical competences. A curriculum which tried to meld property law and client counselling is apt to do neither justice. It won’t make the study of complex conceptions of ownership any clearer, nor illuminate the under-researched practice of client engagement. Often, this type of approach appears to be more about marketing the practical credentials of an academic degree and implementation of university “employability” agendas, than inspired curriculum innovation.

But if the SQE prompts us as legal academics to re-examine the connection between academic law and the social reality of law, that can only be a good thing. And in a similar way, the SQE could also be a service to postgraduate legal education. The ubiquitous LPC, despite its ridiculous construction and regulation has provided lucrative opportunities to many providers for years.

This broadly homogenous product, whose content is not driven by research or an empirical evidence base, has propagated a certain type of student and a particular species of academic. The utility of the education and the foundations upon which it is based might be debated. What is certain is that modern legal practice needs research, scholarship and postgraduate learning opportunities which will help it keep pace with the complexities in society and the evolving challenges of justice. This is not something that the LPC in its current format readily promotes.

SQE2 strips away the link between the validation of practice competencies and postgraduate professional education that has been a financial lifeline for many law schools. However, it has also had a stranglehold on universities preventing them from developing truly useful, research-informed postgraduate provision that meets the needs of a diversified legal sector and a failing system of justice. LPC staff can now perhaps develop their place as postgraduate educators, enjoy the benefits of research-led teaching, develop as scholars and face the challenge of building curriculum which is genuinely of value.

More importantly, law students might start valuing learning, rather than certification and bring real value, rather than trained competences, into the justice system. At De Montfort Law School, the SQE has prompted this type of debate and catalysed the development of a fundamental shift in what we are teaching and the way we teaching it. We look forward to rolling out our new learning opportunities through the coming year in line with the anticipated timeframe for SQE.

I was a skeptic at first, but if it provides the impetus for innovation in professional legal education and forces us to make the case for law as a university subject, then the SQE is the best thing to happen to university legal education in decades.

Professor Kevin Bampton is head of Leicester De Montfort Law School. He will be speaking at LegalEdConNorth on 30 January in Manchester.