Could it happen here in the UK?

Today is the new term of the US Supreme Court; new pencil cases are at the ready but the court has a vacancy, only eight spaces are filled.

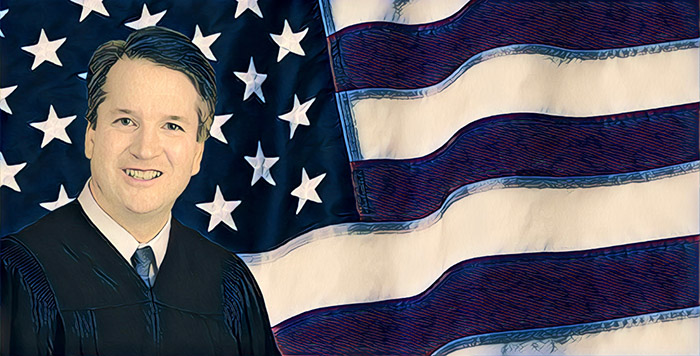

Enter Brett Kavanaugh, the lawyer nominated by President Trump to become the ninth justice. It is his job interview for the post that has dominated airtime over the past week when Professor Christine Blasey Ford shared her story of how she says Kavanaugh sexual assaulted her when they were teenagers. The impassioned speech made before a po-faced Senate Judiciary Committee’s eight-hour sitting enraptured the world’s media and set social media alight.

"I am here today not because I want to be. I am terrified. I am here because I believe it is my civic duty to tell you what happened to me while Brett Kavanaugh and I were in high school" – Christine Blasey Ford gives testimony in #KavanaughHearings https://t.co/RGLhzWMovX pic.twitter.com/u2E6ST0EKt

— BBC Breaking News (@BBCBreaking) September 27, 2018

In the next week or so the Senate will vote on whether or not to approve Trump’s nomination: the world holds its breath. Whether or not Kavanaugh is appointed, however, the events of the past few days in the committee are nothing short of frightening. To see publicly, how an appointment of one of the most important jobs in the judiciary in one of the most dangerous countries in the world, is turned into a political circus and populist show.

Why is it so lunatic? It is partly simply because in the US it matters so much. The US Supreme Court is very powerful in its interplay with the US Constitution and primary legislation and individual justices stay around a long time (one judge has been sitting for over a quarter of a century!): this candidate could change the conservative-liberal make-up of the US supreme court for a generation.

But it is also about the process: US Supreme Court justices are put forward by the incumbent President of the US. In the UK, though the Prime Minister is the official appointee of a UK Supreme Court judge (along with the Queen), a judicial selection committee does the hard grafting of selecting and vetting candidates. That judicial committee includes the current President of the UK court and also must have one non-lawyer. Though one cannot say that any system is entirely apolitical, the US system is so blatantly partisan that it makes a mockery of any attempt at objectivity.

Then it is the “transparent” vetting process the US enjoys whereby a committee of politicians (again, those meddling politicians!) is given the opportunity ostensibly to ensure that the President’s nomination is of good character. But what happens is that we get days and days of partisan digs being made of the nominee. In the case of Kavanaugh, we had a shocking revelation that he had been accused of sexual assault (we can’t call it testimony because, remember, this was not a criminal trial, this was an interview for a job).

The Independent has argued today that it is actually the UK system which is flawed for not having this level of transparency, bizarrely finding itself taking the same line as the Daily Mail which famously declared UK Supreme Court justices as “enemies of the people” and claimed that it was all the fault of a UK appointment system that was “opaque” and “behind closed doors” (it is so obvious when people who don’t agree with what judges say and decide, argue that the system that appointed those judges is flawed).

But it is very hard to see how the US public learnt anything through the Kavanaugh-Ford debacle: the senate committee had absolutely no desire to uncover the truth about or the moral character of a candidate (nor did anyone on Twitter). Everyone had already taken sides in an increasingly polarised, increasingly angry and tribal America. As a US writer brilliantly summarised it: “truth was not the goal, nor will it be the outcome.”

Let’s not forget either that the US Supreme Court already has a Trump nominee, also chosen in extremely murky circumstances. In 2016, Barack Obama had nominated Merrick Garland, a liberal judge, for a vacancy at the time, but a republican senator simply refused to hold the hearings for Garland and so the candidacy lapsed when Obama left office. That led to Neil Gorsuch, Trump’s appointee, getting the job.

Of course, what happened to Garland was an abuse of process rather than the process itself being flawed, but the stonewalling of Garland’s nomination demonstrates perfectly that cold, hard politics is the only thing at play here.