We pick up the trail of the female suffrage campaigner coined ‘Queen of the Mob’ by the press, 100 years after (some) women got the vote

Aged 26, Christabel Pankhurst achieved something we’re sure many of our law student readers will be jealous of: a first-class degree in law. What she couldn’t do, however, was practise law with it.

The daughter of a barrister, Christabel had wanted to follow in her father, Richard Pankhurst’s, footsteps. He was called to the bar, specifically at Lincoln’s Inn, in 1867, having previously studied law at the University of London.

But she wasn’t afforded the same opportunity. Despite having a top-class degree from what would go on to be a Russell Group university, the Victoria University of Manchester, Christabel’s gender meant she was unable to, legally, become a lawyer. This was the case when she graduated in the early 1900s, despite women having been able to study for law degrees since the 1870s.

Christabel, unwilling to accept being barred from the bar, contacted Lincoln’s Inn in 1904, a year into her law degree. Two years before that, an administrative error saw Gray’s Inn accidentally admit a woman, Bertha Cave, to the bar, though it later corrected this.

Lincoln’s didn’t make the same mistake. Christabel’s petition to join the Inn was put before council in January; minutes of the meeting note, bluntly, she “was refused”. The reason for this, Doughty Street Chambers‘ Helena Kennedy QC in her book Eve Was Framed says, was “a disturbing resort to discriminatory practices in the application of the law”.

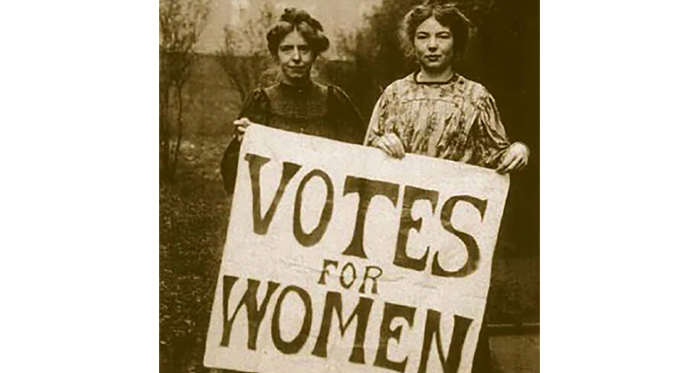

Dismissed by Lincoln’s Inn, Christabel intensified her campaign for female voting rights, alongside her mother, Emmeline. The pair had already founded a campaign group several years before Christabel’s graduation: its members would go on to become known as ‘the suffragettes’.

Frustrated by the slow progress made by their more passive forerunners, the suffragists, the suffragettes were more militant in their approach to campaigning. They lit fires and detonated bombs; many were arrested and imprisoned on several occasions.

Christabel, dubbed ‘Queen of the mob’ by the media, was one of the most vociferous and controversial suffragettes of them all. She was arrested multiple times and sent to prison, too. This habitual law-breaking is perhaps not what you’d expect from a law graduate and aspiring barrister. But, at one trial, she said her actions had “no selfish motive”:

“I have no personal end to serve, neither have any of the other women who have gone through this court during the past few weeks, like sheep to the slaughter. Not one of these women would, if women were free, be law-breakers.”

She clearly had her supporters. A biography written by June Purvis, a professor of gender history at the University of Portsmouth, writes of “overwhelming cheering” at Christabel’s graduation. Though a member of the congregation had shouted at Christabel as she entered the stage (“Why have you not brought your banner?!”), the interruption was soon drowned out by raucous applause. It was a “response that must have made Emmeline glow with satisfaction”, says Purvis.

The female suffrage movement led, 100 years ago, to a pivotal change in the law. The Representation of the People Act, which garnered Royal Assent in February 1918, saw about 40% of women enfranchised — this based on age, status and education. The new law paved the way for, in 1928, all British women older than 21 to be granted the right to vote.

Did Christabel’s law degree help this along? It’s difficult to prove a link but, as Dana Denis-Smith, founder of the First 100 Years project, a celebratory campaign to mark the year when women could practise law, says:

“Legal education would have helped her construct arguments and understand legislation for sure; also wanting to be a barrister meant that she was interested in advocacy which would have served her well.”

One year after the Representation of the People Act, in 1919, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act came to be, allowing women to practise law.

In 1920, Madge Easton Anderson became the first woman admitted as a solicitor; Ivy Williams was the first woman called to the bar. The first female silks came in 1949, and female law professors in the 1970s, the First 100 Years’ timeline shows. More recently, Fiona Woolf became the first female partner at a City firm, CMS, in 1981, and Brenda Hale, in 1984, was the first woman appointed to the Law Commission.

Christabel, despite scoring a first-class law degree, is not on this list of trailblazing female lawyers, though. In the years following the 1918 and 1919 acts, she turned her hand to Christian fundamentalism. She headed across the pond to join the Christian ministry, where she wrote and lectured on religion.

“Many feminists who have thought about [Christabel’s] life have wished that she would have used the second half of her life to blaze a trail for women in the legal profession,” says historian Timothy Larsen. Historian and author Martin Pugh puts it more curtly: Christabel “never quite achieved all that she was capable of during her adult life”, he thinks.

Christabel’s decision not to pursue a career at the bar, Denis-Smith suggests, may lie in her hipster personality. “It was probably less attractive [to Christabel] to be mainstream,” she says; “it was very attractive for a campaigner to push down the boundaries, but less exciting once the rules changed and women could become members.”

And besides, it’s not as if Christabel did nothing with her life post-1918. Larsen, an expert in historical theology, heaps Christabel with praise for joining the Christian ministry when it was “most badly in need of being wrested away from a male hegemony”. He says:

“[Christabel] went into a profession that was male dominated and carved out a place for herself in that world, not just as a participant, but as a star.”