Ditching dusty books for coding courses

Ten years ago, ‘futurologist’ and tech expert Richard Susskind wrote his famous, and controversial, The End of Lawyers?, in which he argued that technology is and will continue to drastically change the legal profession. Since then, we’ve seen all manner of ‘rise of the robot lawyers’ headlines, including ‘The robot lawyers are here — and they’re winning‘ by the BBC‘s technology correspondent, and ‘Will lawyers be replaced by robots?‘, by the then president of the Law Society.

The jist of these headlines and the words beneath them is that technology’s growing sophistication means it is beginning to encroach on the work of lawyers and paralegals. Some of this is speculative, such as the Law Society’s prediction automation could cause 67,000 job losses. But some is more perceptible: we have robot lawyers that can review documents, that can draft parking fine claims and that can predict human rights case outcomes. “Lawyers all over the world should be very scared of this technology,” computer science student and creator of the DoNotPay robot tells Legal Cheek.

Lawyers have encouraged students to use this fear as a catalyst. Students have been told by a host of big names at various Legal Cheek events to, at a minimum, be mindful of the impact of technology in the law or, better, actively prepare for it, such as by learning to code. An advice piece, ‘Ready for robot lawyers? How students can prepare for the future of law‘, published in The Guardian encouraged law students to seek internships at tech companies like Google and to study modules with internet and cyberspace content.

You can forgive students for saying “thanks, but no thanks” to this advice. I would’ve done as a student: the traditional study of law mixes with technology like oil does with water. If I’d wanted to play with technology I would’ve done a computer science degree, but I wanted to read old dusty books that I have to climb up a library ladder to reach, thank you very much. And who has time to code in between all that crying about the Unfair Contract Terms Act, anyway?

This is certainly a view shared by a number of students I spoke to for this piece (though perhaps in not-so-sassy terms). “Personally, I did not consider [the impact of technology] when I entered into my legal studies and it is not an issue which is at the forefront of my mind when I think of my future prospects in a legal career,” reports one law student. “For sectors of law such as criminal law in particular, it is hard to be convinced that tech can triumph.”

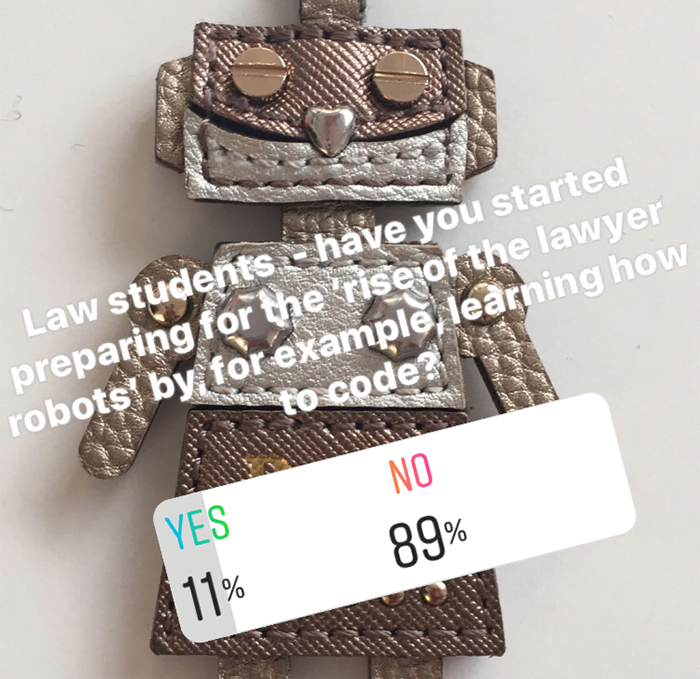

I’m unsurprised, then, that a recent Legal Cheek poll painted law students as techy blasé. Of the 1,400 who answered when asked “have you started preparing for the ‘rise of the lawyer robots’ by, for example, learning how to code?”, just 11% said yes.

But, despite this pervading nonchalance, the survey shows 160 respondents have heeded lawyers’ ’embrace innovation’ warnings.

Tech enthusiast Izaan Khan is doing just that. A student at the London School of Economics with “a profound interest in the way technology interplays with the law”, Khan has learnt to code alongside his degree. He explains to Legal Cheek that this “has taught me to solve general problems using the same methodical and analytical mindset, while also pressing me to find better alternatives to solutions I do come up with”. Ultimately, he intends “to be the officiant in the marriage between technology and law”, he says.

Also hailing from LSE is Kimia Pezeshki, a self-confessed “technophile” who completed the Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL) in 2016 and is now an in-house paralegal.

Her passion for innovation and technology began while she was at university but has manifested itself more recently in the creation of a podcast, Law Meets Tech, which she launched in January 2018. She says:

“The legal industry is very hard to penetrate, especially for those who do not fit the socio-economic prototype historically favoured by old-fashioned English law firms. It’s a good idea for all young people, particularly those of us who don’t fit the mould, to diversify our skillsets, be that in technology or otherwise.”

While our two LSE graduates’ avidity for all things techy is clear to see, one group of Cambridge law students have taken things one step further and thrust themselves into the lawtech mix.

Jozef Maruscak, Rebecca Agliolo and Ludwig Bull all either study law or have studied law at the elite university, in this time creating a crime-identifying artificial intelligence (AI) system to “provide confidential, non-judgemental, free, easy-to-understand legal knowledge”. Several rebrands later, the bot recently won a ‘man vs machine’ case-predicting challenge, which involved guessing PPI claim outcomes. Rise of the robot lawyers? Rise of the robot law students, more like.

But don’t think you have to be smashing case-predicting challenges to position yourself in the lawtech game. On the more manageable end of the tech-enthusiasm scale, a number of law students have taken the view that a simple understanding of technology’s place in law and a good grasp of IT isn’t a bad thing. One student, speaking to me for this piece, thinks it’s fundamental young lawyers can use simple technological tools to help prioritise time and cultivate client relationships, while another says they’re attending workshops on Excel and cloud accountancy.

For BPP Law School students, this more gentle approach to honing their technology skills doesn’t have to be discrete to their studies.

Just recently, Legal Cheek reported the law school giant had introduced a new module on its Legal Practice Course (LPC), the aim of which is to “equip students not only with the digital skills the legal practice of the future will need, but also the ability to use and design technology to respond to problems”.

To end this article where it began we turn to the views of Susskind, who has long been pushing for law schools to better equip their students for future legal practice with more tech content on their courses. BPP’s move, having been made in a very competitive postgraduate course provider market, may encourage others to follow suit. The army of robot law students grows.